State capacity is important for economic development, but the economic history of state building is understudied and until recently, it disproportionately represented Western Europe and Western offshoots. In recent years, new research has widened our knowledge of colonial states’ capacity to levy public revenue, especially in the British empire (Bolt & Gardner 2020), with some comparative analyses with the Belgian and French empires (see Booth 2007, Gardner 2013, Frankema & Booth 2019, Van Waijenburg 2019).

Three important questions on colonial states are not completely settled in the existing literature: i) How fiscally extractive were colonial states? ii) What was the capacity of colonial states to provide public goods and services? iii) As the intentions of colonialism appeared to change in the last 15 years of colonization – the era of “developmentalist colonialism” (Cooper 2002) – did this capacity change? The reason why these questions are not settled is that they come with specific methodological challenges, particularly in terms of data availability. In a recent article (Cogneau, Dupraz & Mesplé-Somps 2021), we contribute to answering these questions, taking the French empire as a case study.

A New Database on Colonial States

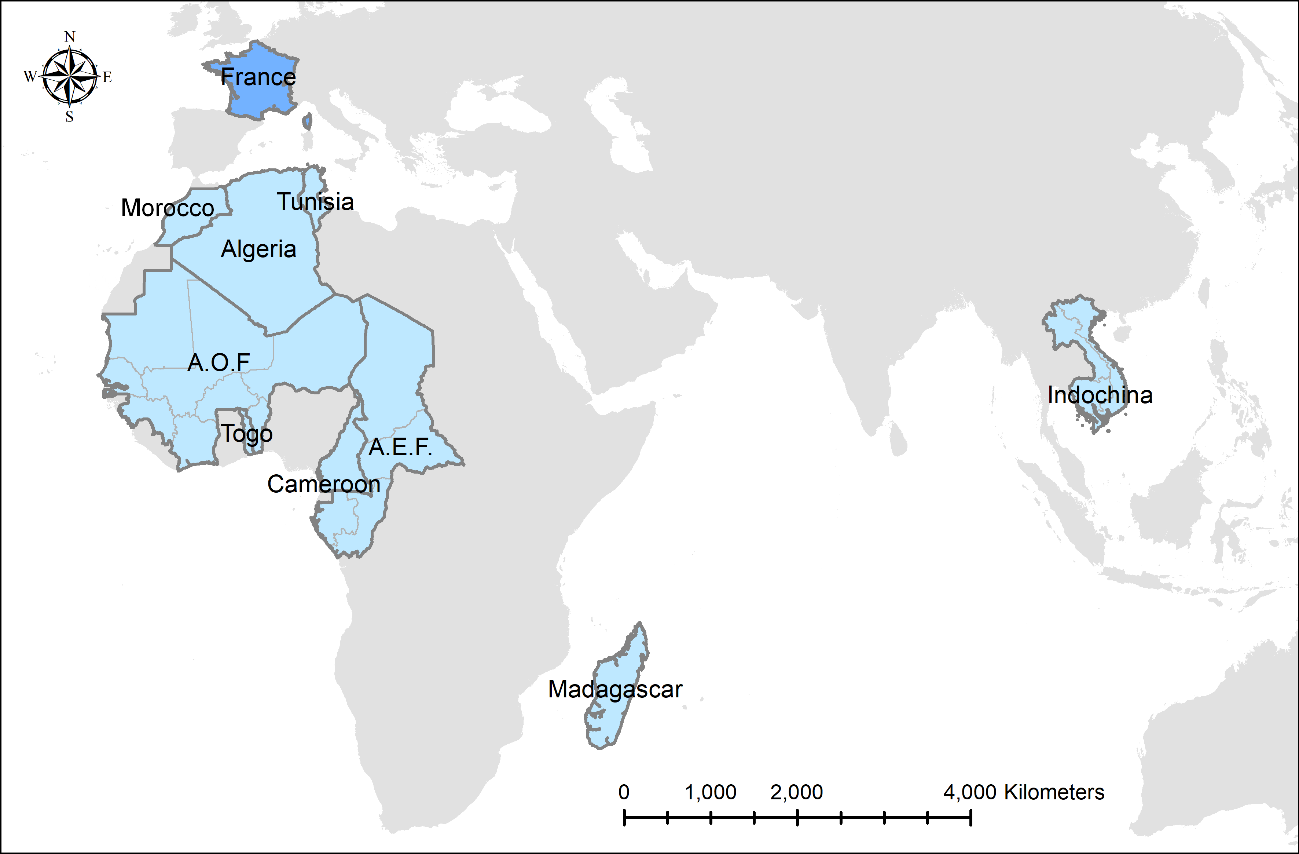

We created a new database on French colonial states from the beginning of colonization to independence. This corresponds to 21 present-day countries in North Africa, sub-Saharan Africa, and Southeast Asia (see map below).

We collected annual revenue data from approximately 1,700 primary sources for the period 1830-1962. We mainly used detailed definitive budget accounts, taking into account all public authorities responsible for revenue and expenditure in the French colonies, and all sources of public revenue. Public revenue and expenditure variables were consolidated to avoid double counts arising from transfers between different administrative layers. We produced estimates of GDP per capita in the French empire to express fiscal extraction in GDP shares. From statistical yearbooks, we also collected development outcomes and policy variables such as school enrollment, health personnel, electricity output, road or railway length, and international trade.

This database can be downloaded here.

Figure 1: Colonial territories present in our data

Fiscal Extraction: High and Adapted to Local Economic and Social Conditions

We find that colonial states of the French empire had substantial extractive capacity. On average, they extracted 9% of the colonies’ GDP in 1925, and 16% in 1955. We show that these figures were above the average at the same date for non-colonized countries in the same range of income per capita . This high fiscal extraction was not a French specificity, but rather a general characteristic of colonial states in the 20th century, whether French, British, or Japanese, and despite important exceptions like British India or Nigeria, which stood out by their low fiscal capacity.

The French adapted the fiscal structure to local economic and social conditions: in the settler colonies of North Africa, they used more modern tax systems, like the income tax; in Indochina, monopolies, especially the monopoly on opium, provided large revenues; in sub-Saharan Africa, the French relied on the head tax (capitation) and forced labor.

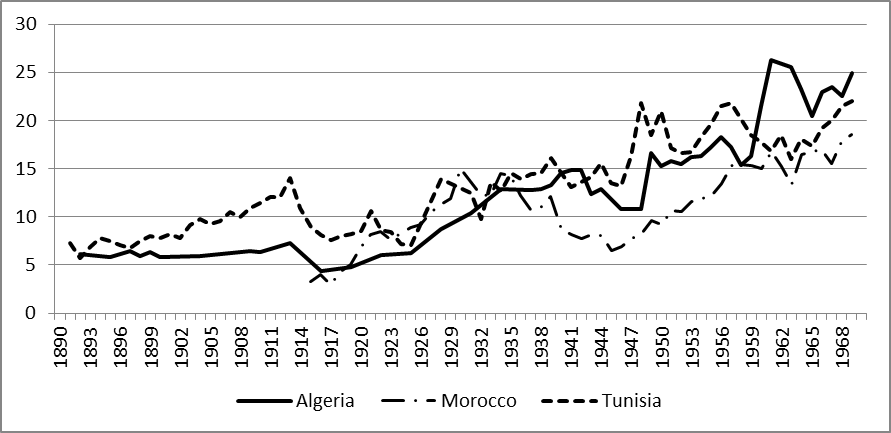

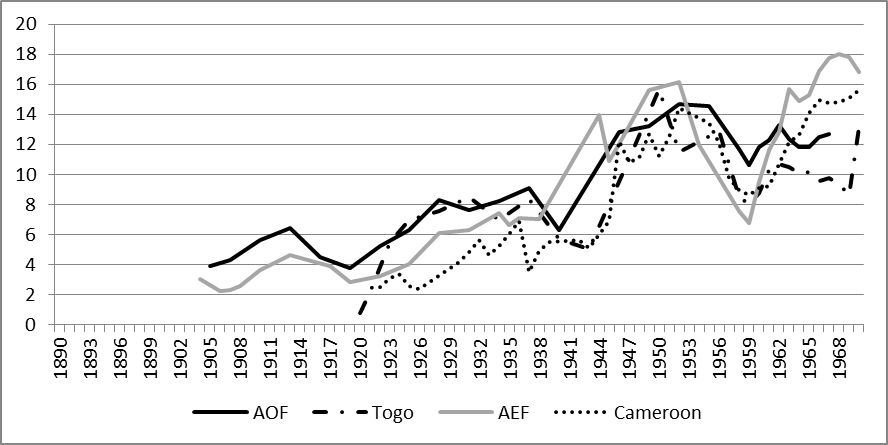

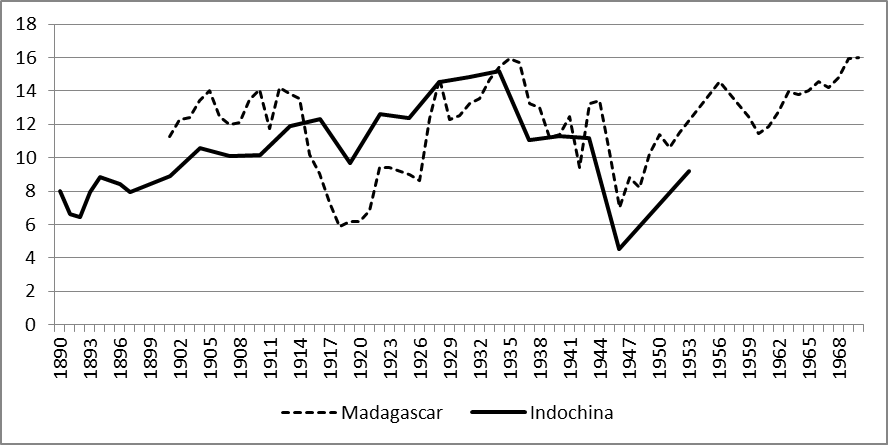

However, even if local conditions mattered a lot for the type of fiscal instruments used, fiscal extraction was high in all French colonies, and the tax burden weighed heavily on local populations. Figure 2 shows the evolution of net public revenue as a share of GDP between 1890 and 1970 in each colony or federation.

Figure 2: Net public revenue as share (%) of GP, 1890-1970

Notes: The revenue of first-level administrative divisions (provinces, départements, régions) is included and consolidated, but not the revenue of second-level administrative divisions (municipalities). Estimates of corvée labor revenue are not included in the figures for West and Central Africa and Madagascar. Source: See online Appendix 1, Cogneau et al. (2021).

High Wage Cost and Biased Expenditure

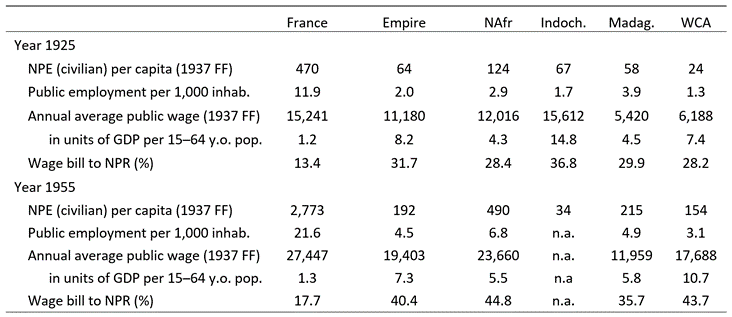

In a context where local populations had almost no ability to influence colonial governments before World War II, the extractive capacity of colonial states and their capacity to provide goods and services useful for development did not necessarily go hand in hand. We show that due to high wage costs, in particular the wages paid to European civil servants, colonial states did not transform high fiscal capacity into high spending capacity, and that French colonies were under-administered. In 1925, the average government employee in the French empire was paid about nine times the colonial GDP per worker, and the number of government employees per inhabitant was six times lower than in metropolitan France (see Table 1). On top of this, public expenditure disproportionately favored the needs of European settlers and firms. In Algeria, for example, European settlers represented only about 10 percent of the population yet received about 80 percent of total education expenditure.

Table 1: Public employment and wages in 1925 and 1955

Source: See online Appendix 1, Cogneau et al. (2021).

Disappointing Achievements during the Developmental Era

After WWII, as the legitimacy of French rule became increasingly questioned, its colonial governments did not tax and spend less. On the contrary, they taxed and spent more. In the hope of preserving their imperial dominance, they became more developmental. They increased social spending, particularly in education. They gave some political rights to local populations, adopted somewhat more progressive taxes, and conceded some wage equality claims. The self-financing doctrine was relaxed, and net grants from metropolitan France started representing a larger share of the colonies’ GDP. Wage costs, however, remained high. The public sector wage premium, measured as the ratio of average public wage to GDP per working-age person, increased between 1925 and 1955 (see Table 1). Given these high unit costs, accelerating development would have required an even bigger push in French grants.

After independence, the modern African/Asian states inherited the structures of their former colonial states. Some preserved high wages and elitist infrastructure. Others opted to extend public employment and decentralize at lower costs. Further research is warranted to analyze these postcolonial evolutions.

References

Bolt, Jutta and Leigh Gardner (2020). “How Africans Shaped British Colonial Institutions: Evidence from Local Taxation.” Journal of Economic History 80(4): 1189-1223.

Booth, Anne (2007). Colonial Legacies: Economic and Social Development in East and Southeast Asia. University of Hawaii Press.

Cogneau, Denis, Yannick Dupraz and Sandrine Mesplé-Somps (2021). “Fiscal Capacity and Dualism in Colonial States: The French Empire 1830-1962.” Journal of Economic History. doi:10.1017/S0022050721000140.

Cooper, Fredrick (2002). Africa since 1940: The Past of the Present, Cambridge: Cambridge University

Frankema, Ewout and Anne Booth (2019). Fiscal Capacity and the Colonial State in Asia and Africa, c. 1850-1960. Cambridge Studies in Economic History.

Gardner, Leigh A. (2013). “The Fiscal History Of The Belgian Congo In Comparative Perspective.” In Frankema, Ewout and Franz Buelens (eds), Colonial Exploitation and Economic Development: The Belgian Congo and the Netherlands Indies Compared, London: Routledge, 2013.

Van Waijenburg, Marlous (2018). “Financing the African Colonial State: The Revenue Imperative and Forced Labor.” Journal of Economic History 78(1): 40-80.

Feature image: File:AOF-Dakar-Palais du Gouvernement.JPG – Wikimedia Commons