The Persistent Influence of Chiefs

Our focus on chiefs, as opposed to the formal state, is a notable departure from much of the current literature on the determinants of corruption. Even though state capacity is considered an important precondition for economic development, central states in contemporary Africa tend to be weak. Chiefs remain influential on a wide range of governance issues (Michalopoulos & Papaioannou 2020). In their role as custodians of land, chiefs often exert influence over the allocation of land and the distribution of land rents. Chiefs in many countries also enter into deals with mining companies on behalf of rural communities, regularly resulting in serious corruption allegations. Further, chiefs engage in governance roles, such as the administration of justice and contract enforcement, the collection of taxes, and the provision of public goods. In addition to their direct role in local governance, chiefs exert influence on the central state via lobbying as well as mobilizing their local networks and resources for election campaigns. They also interact with the central state, acting either as substitutes or complements to the central state. Thus, a focus on chief is well-warranted since their accountability is likely to have considerable implications for the quality of governance and economic development in many African communities.

Chiefs in British versus French Africa

In our recent paper, we focus on the legacy of British versus French colonial rule on the corruption of chiefs in Africa. The ‘legal origins literature’ associates British rule with lower levels of corruption, as compared to that of French rule (La Porta et al. 2008). It underscores the supremacy of the British legal system in ensuring the accountability of state institutions, such as the executive and the judiciary. However, in colonial Africa, much of the control happened through chiefs, rather than the central state. Hence, the formal legal systems introduced by the colonial powers, while mostly applicable to the central state, had limited relevance for governing much of the population. Many scholars of African political economy also emphasize the limited role of the central state in much of their hinterlands (Herbst 1989).

An important feature of British rule was the considerable autonomy that it offered chiefs in ruling the local population while shifting their accountability primarily to their colonial master, as opposed to the local population (Mamdani 1996). This undermined precolonial constraints on the chiefs’ abuse of power and empowered them over the population. In contrast, the French colonial policy systematically undermined the power of chiefs (Crowder and Ikdime 1970). They were stripped of the power to appoint sub-chiefs and handle legal matters. As agents of the colonial power, their primary task was to collect taxes and recruit labor. Unlike their British counterparts, their control over the expenditure of the budget and land resources was limited, which diminished their opportunity to distribute rents and extend patronage networks.

Data and Findings

Using data from the nationally representative Afrobarometer surveys for 9 francophone and 12 anglophone countries we examine the empirical relationship between British versus French colonial rule and the corruption of chiefs. Our sample consists of more than 40,000 observations. We examine two outcome variables from the survey data. The first variable measures the prevalence of corruption among chiefs and is based on respondents’ perceptions of the extent of corruption by traditional leaders in their community. The second outcome variable reveals the level of public trust in traditional leaders.

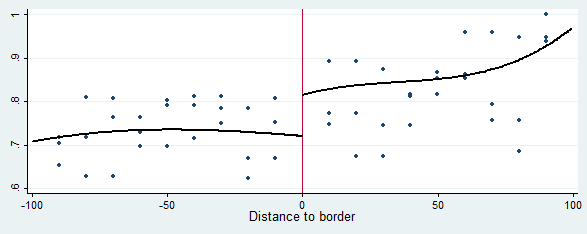

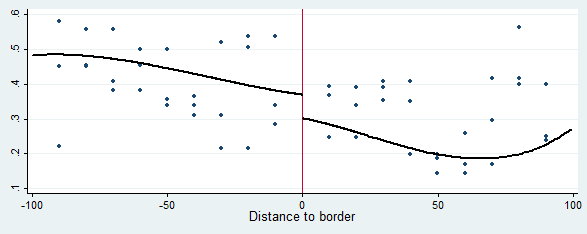

We find that corruption among anglophone chiefs is perceived to be significantly higher than among francophone chiefs. We also find a significantly lower level of public trust in anglophone chiefs. The results are robust across alternative specifications and samples. They hold in the sample of all observations in our data, as well as a regression discontinuity (RD) analysis that focuses on observations near the national borders in West Africa, where ethnic homelands were split between anglophone and francophone countries.

The figures below present a visual display of the level of corruption and trust, respectively, as one crosses the anglophone–francophone borders in the sample. The fitted lines represent the correlation between distance to national borders and corruption of chiefs (Figure 1) and trust in chiefs (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Corruption of chiefs in West Africa, by distance to anglophone–francophone borders

Notes: The figure shows, by distance (in km) to the border, the share of respondents who report that chiefs are corrupt. The distance from the francophone–anglophone border increases as we move away from the center point (0) on the x-axis. Negative (resp. positive) values represent distance from the border into francophone (resp. anglophone) territories.

Notes: The figure shows, by distance (in km) to the border, the share of respondents who report that chiefs are corrupt. The distance from the francophone–anglophone border increases as we move away from the center point (0) on the x-axis. Negative (resp. positive) values represent distance from the border into francophone (resp. anglophone) territories.

Figure 2: Trust in chiefs in West Africa, by distance to anglophone–francophone borders Notes: The figure shows, by distance (in km) to the border, the share of respondents who report that chiefs are trustworthy. The distance from the francophone–anglophone border increases as we move away from the center point (0) on the x-axis. Negative (resp. positive) values represent distance from the border into francophone (resp. anglophone) territories.

Notes: The figure shows, by distance (in km) to the border, the share of respondents who report that chiefs are trustworthy. The distance from the francophone–anglophone border increases as we move away from the center point (0) on the x-axis. Negative (resp. positive) values represent distance from the border into francophone (resp. anglophone) territories.

These empirical patterns suggest that the empowerment of chiefs under colonial rule has a more potent legacy than the formal legal system that colonizers left behind. Our finding of a positive association between British rule and the level of corruption among chiefs underscores an important qualification to the empirical patterns in the existing economics literature on the legacy of British rule on corruption.

References

Ali, M., Fjeldstad, O.-H., Jiang, B. and Shifa, A. (2020). European Colonization and the Corruption of Local Elites: The Case of Chiefs in Africa. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 179: 80-100.

Crowder, M. and Ikime, O. (1970). West African Chiefs: Their Changing Status under Colonial Rule and Independence. New York: Africana Publishing Corporation.

Herbst, J. (1989). The Creation and Maintenance of National Boundaries in Africa. International Organization 43: 673–692.

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F. and Shleifer, A. (2008). The Economic Consequences of Legal Origins. Journal of Economic Literature 46: 285–332.

Mamdani, M. (1996). Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Michalopoulos, S. and Papaioannou. E. (2020). Historical Legacies and African Development. Journal of Economic Literature 58: 53–128.

Featured image: Engraving depicting an African Chief seated in State among his Headmen. Dated 19th Century

Contributor: World History Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

Downloaded from: Engraving depicting an African Chief seated in State among his Stock Photo – Alamy

Very insightful work. The bequithed institutions like judiciary, police and systems could also enlighten on the persistent post-colonial corruption. Thanks very much for the stimulating work