Political institutions and the balance of political power strongly influence the evolution of economic institutions, making them important for economic growth. The nature of political institutions and the distribution of political power and influence, in their turn, can be significantly affected by major events (Acemoglu, Robinson & Johnson 2005). As I show in my article, political institutions in Africa were substantially affected by such a major event, the trans-Atlantic slave trade (Obikili 2016a).

Long-run effects of the trans-Atlantic slave trade

Although Africa is not unique to the trading of slaves, the magnitude of slave exporting rose to levels not experienced anywhere else in the world. Between 1500 and 1900, an estimated 10 million slaves were exported from West and Central Africa, mainly to the Americas, a figure that excludes people who died either during capture, the long trek to the coast, or the journey across the Atlantic. To put this in further perspective, the estimated population in 1700 of the exporting regions was only about 28 million people. We may expect an event of such magnitude to have long-lasting social, political and economic effects. Many researchers have tried to uncover these effects with some degree of success. Some have found that relatively higher slave export intensity is associated with relatively lower GDP in more recent times. Higher slave exporting societies have also been linked to lower levels of trust, lower levels of subsequent education, and a range of other negative social outcomes (Nunn 2011; Nunn & Wantchekon 2011; Obikili 2016b).

The slave trade and political fragmentation

From a political institutions perspective, authors have found that areas with relatively higher slave export intensity had higher levels of political fractionalization after the slave trade ended. The slave trade created opportunities for wealth generation for anyone who could mobilize people to raid other towns and villages or organize kidnappings, creating significant political friction in the process, which even led to the breaking up of political units. For instance, it has been argued that the slave trade was partly responsible for the wars that led to the break-up of the Yoruba state (Bowen 2006). Indeed, researchers have also found statistical evidence that areas that had higher slave-trading intensity tend to have a higher proportion of distinct groups today (Whatley & Gillezeau 2011).

In this article, I hypothesize that the same kind of political friction caused by the slave trade should also have influenced political institutions on village- and town-level. While states may break up as a result of political friction, such a breakup is impractical in the case of villages or towns as, except in very rare cases, their inhabitants are geographically bound together. I argue, therefore, that, villages and towns tend to form more political groups in response to political friction. Such political groups serve to protect their own members and take advantage of members of other groups

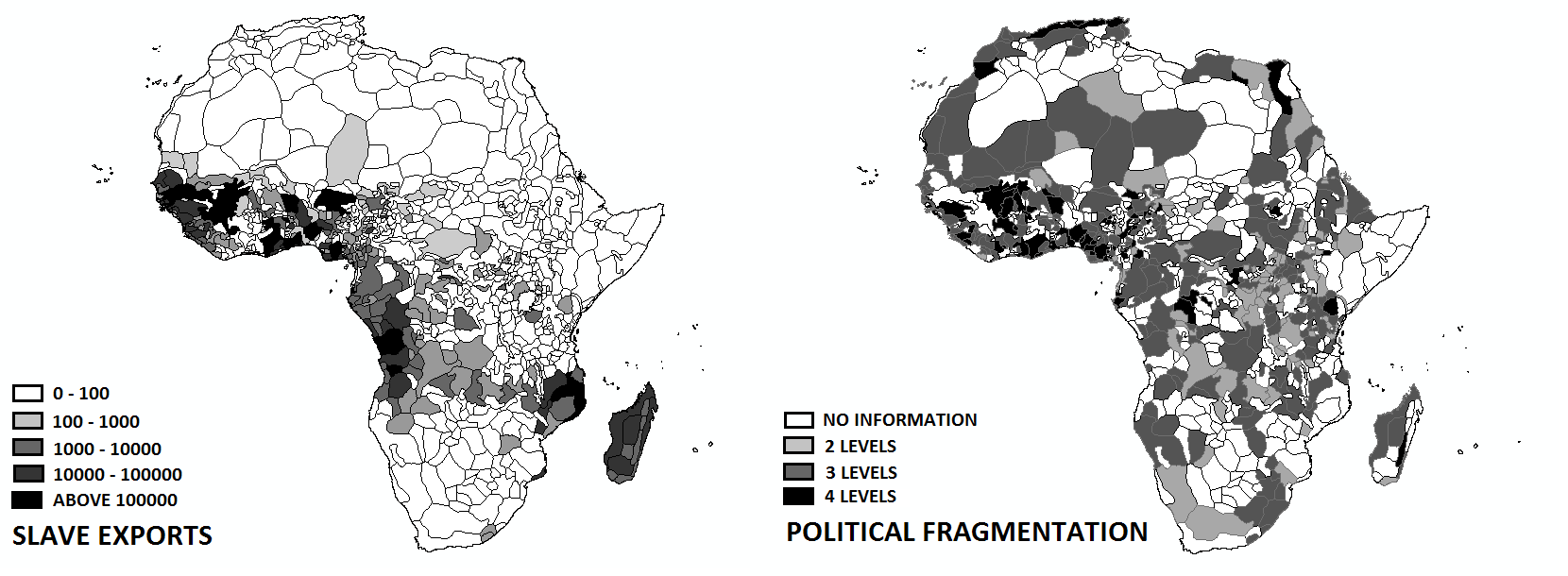

Using slave export data and anthropological data from Murdock’s ethnographic atlas, particularly the variable capturing jurisdictional hierarchy within the local community, I find that places with higher historical slave export intensity did have more fragmented political structures in villages and towns at the time they were recorded by Murdock, roughly between 1900 to 1960 (see Figure below). I use the distance to slave ports in the Americas as instrument to show that slave exports did influence local political institutions, causing them to be more fragmented.

Figure: Slave export intensity and political fragmentation in Africa

Contemporary effects?

Do the effects of this historical political fragmentation still show up in contemporary times? I use data on bribery from the Afrobarometer surveys to answer this question. Bribery is a typical means of rent extraction by political groups, and it is expected that towns with more political groups should imply more bribes, especially if power is distributed relatively evenly between political groups. I focus on Nigeria and Tanzania because only both countries had survey data across a significant number of ethnic groups and to isolate colonial era effects. I find that areas with more fragmented political institutions prior to the colonial era show higher incidences of bribes paid for documents or household services in Nigeria and Tanzania.

It is important to note that the effects of political fragmentation should not be thought of as a decidedly negative. The introduction of checks and balances and more equally distributed political power have proven to be essential components of political progress. At the same time, however, fragmented societies might find it more difficult to implement checks and balances or redistribute political power since broad coalitions are required, and such coalitions are more difficult to establish in more politically fragmented societies. The effect of political fragmentation is thus likely to depend on the specific context of the society, and, as with all historical studies, the findings do not imply that the outcomes are permanent. This paper has demonstrated that a major historical event such as the transatlantic slave trade has long-term consequences on the local level, a finding that should motivate researchers to better understand how political institutions respond to such events.

References

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., and Robinson, J. A. (2005) “Institutions as a fundamental cause of long-run growth”, in P. Aghion and S. N. Durlauf, eds., Handbook of Economic Growth, Vol. 1A, pp. 385–472

Bowen, T. J. (1968), Adventures and missionary labours: in several countries in the interior of Africa. London, Cass.

Nunn, N. (2008), “The long-term effects of Africa’s slave trades”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123, pp. 139–76.

Nunn, N. and Wantchekon, L. (2011), “The slave trade and the origins of mistrust in Africa”, American Economic Review,101, pp. 3221–52.

Obikili, N., (2016a) “The trans-Atlantic slave trade and local political fragmentation in Africa“, Economic History Review, forthcoming

Obikili, N. (2016b). “The Impact of the Slave Trade on Literacy in West Africa: Evidence from the Colonial Era“, Journal of African Economies, 25(1), pp. 1-27.

Whatley, W. and Gillezeau, R. (2011), “The impact of the Transatlantic slave trade and ethnic stratification in Africa”, American Economic Review, 101, pp. 571–6.

The Frontiers editorial team consists of Michiel de Haas, Kate Frederick (both Wageningen University) and Felix Meier zu Selhausen (University of Southern Denmark & University of Sussex). AEHN board members Ewout Frankema (Wageningen University) and Morten Jerven (Norwegian University of Life Sciences) form the supervisory board.

We welcome external contributions to the blog and encourage those interested to submit a summary of a recent working or published paper or book review, a commentary on current African developments or something else. Please contact the editors to discuss possible posts at [email protected].