As a landmark of ‘modern’ statecraft and nationhood, census-taking has been central in historical and sociological literature. Following in the footsteps of Foucault (2007) and Anderson (1991), many scholars have explored the capacity of the census to re-make, rather than simply describe, reality. However, this has been done by focusing on the ethnic, religious and racial categories institutionalized by the statistical apparatus. This article suggests that this narrow focus limits our understanding of the multiple ways in which counting people feeds into processes of political imagination and transformation. The case study of Ghana’s first postcolonial census is used to shed light on the public discourse and cultural representations associated with population counting in post-colonial Africa.

The ‘first modern census of contemporary Africa’

The 1960 Population Census of Ghana was simultaneously embedded in President Kwame Nkrumah’s vision of national economic and social modernization and in the United Nations’ (UN) mission to disseminate global statistical standards. The count was the first in sub-Saharan Africa to incorporate all the features listed by the UN (government sponsorship, defined territory, universality, simultaneity, individual units of enumeration, and a post-enumeration survey) and was thus greeted as ‘the first modern census of contemporary Africa’.

One of the landmarks of the census’ ‘modernity’ (as envisaged by the UN) was the organization of an extensive census publicity. On the basis of previously unused sources collected in the national archives of Ghana, this article analyses the census propaganda campaign and inscribes it within the authoritarian transformation that occurred under Nkrumah. The story of the census propaganda campaign allows us to unpack the ways in which the global ‘development discourse’ institutionalized by international organizations (of which demographic statistics is an important component) can acquire new meanings through its embodiment in local political cultures. Complementing James Ferguson’s (1994) influential characterization of development discourse and apparatus as an ‘anti-politics machine’, the article shows that the possibility of obtaining people’s trust, without which an accurate census would have been impossible, was intimately linked with the ‘re-politicization’ of the count in the form of a wide range of imaginative representations about the postcolonial state.

Marching children: the elusive contours of grassroots authoritarianism

The capacity of African colonial states to collect accurate population figures was severely limited by issues such as lack of funding, understaffed administrations, and fear of taxation (Frankema and Jerven 2014). Furthermore, from colourful descriptions of fishermen running to sea, to dry accounts of empty villages and riots, Ghanaian archives and government reports abound with instances of resistance to the enumeration. In the aftermath of independence, the ‘Census Education and Enlightenment Campaign’ (1959-1960) was meant to overcome these difficulties. At stake was not only the acquisition of people’s willingness to be counted but, more importantly, the creation of trust in the government. The census thus became a formidable opportunity to produce and disseminate new representations of the state and new political practices.

The UN experts identified school children as the most effective channel to make the people ‘census minded’. Not only did this emphasis on children subvert colonial practices (in which the chiefs and local authorities were charged with the task of explaining the importance of the census to the population), but it also required the production of new content. A series of lessons were given in schools throughout the country. The few lessons that survived in the archives of the Ministry of Education show that the postcolonial state was construed as a benevolent panopticon, a powerful but harmless leviathan built on individual enthusiasm and cooperation rather than fear, and the lynchpin of a modernist iconography that equated measurement with progress. The class activities, combined with the systematic involvement of children in street parades and public events, also reflected the UN conception of the census as the most ‘democratic’ form of statistics, in which each individual mattered regardless of gender, income or social status (Ward 2004, p. 189).

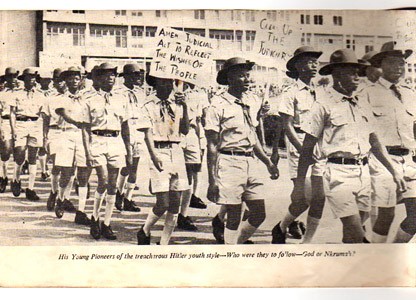

Yet, in Nkrumah’s Ghana, the mobilization of school children evoked dark tales of brainwashing, personality cult and coercion (Ahlman 2017: chapter 3). The Young Pioneers, shown in Figure 1, were perceived as spies reporting to the authorities’ expressions of dissent against the regime, including those of their parents.

Figure 1: Ghana Young Pioneers

It is ironic that the same children who encouraged their parents and their local communities to trust the state and become known to the government by choosing to be counted in the census would become a central trope in the political culture of silence, fear, and suspicion that characterized Nkrumah’s rule. Taken together, the census campaign and the Young Pioneers suggest the fluidity of the political visions for which children were mobilized through remarkably similar practices. This raises uncomfortable questions on how practices prescribed by international organizations acquire a life and political meaning of their own and suggests that scholars must dig deeper into the relationship between ‘development discourse’ and authoritarianism (Easterly 2013).

The press: the census as utopia and political theology

The census also received widespread coverage in the press. Although the official narrative claims that the press’ most important contribution was to ‘depoliticise’ the count by presenting it as a genuinely national operation (Gil and de Graft-Johnson 1964, p. 155), in practice it performed an operation of ‘re-politicization’. With the government exercising an increasingly tight control over newspapers, the party press linked the census with the upcoming referendum which would turn Ghana into a Republic, resulting in a further undermining of parliamentary institutions and vesting even greater power into Nkrumah’s hands.

Hundreds of census-related articles, poems and vignettes carved a role for the census in the history of the nation, either as ‘the second great night of Ghana’ (the first being independence) or as the starting point of a postcolonial utopia free from poverty and illiteracy. In practice, this entailed inscribing the count within the emerging ‘political theology’ built around Nkrumah’s persona.

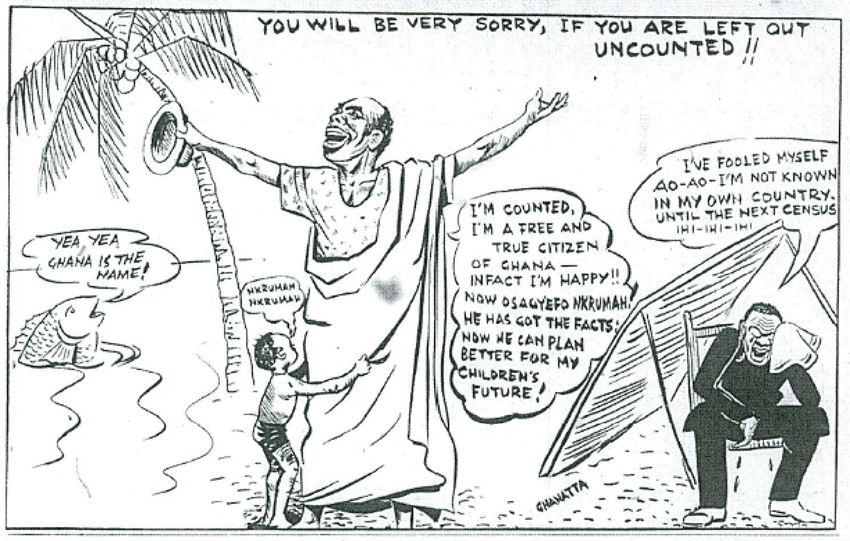

Figure 2: Evening News, 18 March 1960

The newspaper illustration, shown in Figure 2, for example, removed the census from the realm of the state – as a rational and bureaucratic tool – and instead articulated it as a mystical embodiment of the father of the nation, subverting the UN’s emphasis on the technocratic nature of census-taking.

Conclusion: beyond the ‘anti-politics machine’

This article suggests that, far from being confined to statistical offices and the bureaucratic center that created and institutionalized categories and identities, the link between the construction of statistical knowledge and the process of imagining a nation-state can be mediated by other crucial sites of nation-making, like schools and the press.

In Ghana, the task of acquiring people’s trust – without which an accurate enumeration would have been impossible – created the interstitial space between a view of the state as a benevolent entity depending on individual participation, a technocratic agent capable of complex operations of quantification, and a messianic personification of the dictator. By doing so, the education campaign, which found its primary justification in the democratic and technocratic imagination of the UN, stopped working as a cog in the ‘anti-politics machine’ described by Ferguson (1994), and became instead an important – if previously unnoticed- element in the authoritarian evolution of Nkrumah’s Ghana.

References

Ahlman, Jeffrey S. (2017). Living with Nkrumahism: Nation, State and Pan-Africanism in Ghana. Athens (OH): Ohio University Press.

Anderson, Benedict (1991). Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

Easterly, William (2013). The Tyranny of Experts: Economists, Dictators and the Forgotten Rights of the Poor. New York: Basic Books.

Ferguson, James (1994). The Anti-Politics Machine: “Development,” Depoliticization and Bureaucratic Power in Lesotho. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Frankema, Ewout and Morten Jerven (2014). “Writing History Backwards or Sideways: Towards a Consensus on African Population, 1850–2010.” Economic History Review 67(4): 907-931.

Foucault, Michel (2007). Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the College de France, 1977–1978. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gil, Benjamin and K.T. de Graft-Johnson (1964). The 1960 Population Census of Ghana, vol. V: Census Report. Accra: Census Office.

Serra, Gerardo (2018). “‘Hail the Census Night’: Trust and Political Imagination in the 1960 Population Census of Ghana.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 60(3): 659-687.

Ward, Michael (2004). Quantifying the Ward: UN Ideas and Statistics. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.