South Africa’s development path is often regarded as unusual in both global and regional context, although scholars disagree on when and why it diverged. Some have argued that South Africa’s exceptionalism was a consequence of Apartheid policies, starting after the 1920s (Ross, Mager & Nasson 2011). In a recent paper, I argue that South Africa’s exceptionalism has deeper historical roots (Gwaindepi 2021). Using a newly created fiscal dataset, I cast the Cape Colony into comparative fiscal capacity debates to probe how the Cape compares to other 19th-century British settler colonies. I show that the Cape Colony had a divergent path already in the 1880s, with comparatively low per capita taxes, high deficits, and the highest level of indebtedness among the sampled colonies. I explain this through the Cape´s racially discriminatory practices, and the resultant inequalities that restricted the tax authorities to using inferior tax instruments, mainly indirect taxes. Revenues raised through this path of least resistance was inadequate for public goods delivery and debt servicing.

Fiscal Capacity Building

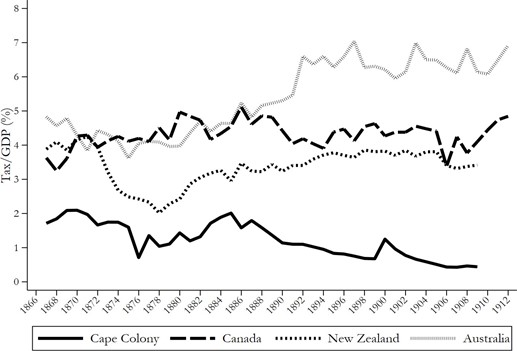

Did South Africa’s tax capacity differ from that of other British settler colonies, which tended to have comparatively high tax burdens? To explore this question, I compare the Cape Colony’s fiscal path to the experiences of other British settler colonies including Australia, New Zealand and Canada. Figure 1 shows the tax to GDP ratios for these four colonies. What is clear is the divergent trend for the Cape, especially from the second half of the 1880s. Australia, Canada and New Zealand managed to maintain modest increases in their tax take, but the Cape’s ratio fell from around two to one per cent. Following the diamond-led economic boom in the 1870s-1880s, the Cape converged slightly with the other colonies, but this tax to GDP ratio growth was not sustained.

Figure 1: Tax/GDP ratios (%): The Cape’s divergent path

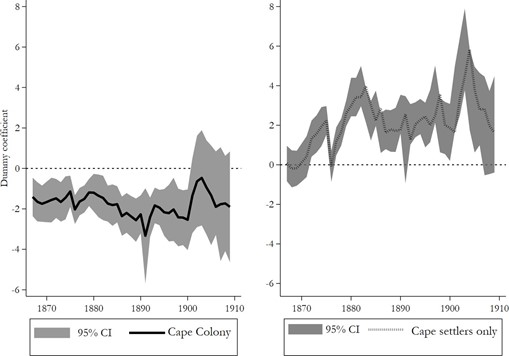

I argue that the Cape Colony´s divergent trajectory is a consequence of a higher indigenous population share compared to the other colonies in the study. Specifically, the Cape Colony’s population composition influenced the development of deliberately exclusionary policies and practices, which limited access and rights of the indigenous population to the colony’s natural resources, mainly land and minerals. This restricted access to resources constituted a key factor in the formal oppression of the indigenous people, with negative implications for the formative years of the fiscal system. Figure 2 below shows the recursive estimates of tax capacity on the Cape dummy when tax per capita is estimated using the total population (left-hand) and the settler population only (right-hand). The estimate considers the differences between the Cape as a whole, and the ‘Cape-settlers’, which only looks at the European settler population.

Figure 2: The Cape Colony’s tax per capita relative to other colonies

The data suggest that limited access to resources reduced the taxable capacity amongst the indigenous majority, despite punitive and extractive taxes such as hut taxes. This ultimately diminished the taxable capacity of the entire economy, especially given that the economic and political elite resisted direct taxes (Gwaindepi and Siebrits, 2020). As a result, the Cape Colony’s per capita taxes were structurally lower than the other colonies. Given that land and mining taxes were important surrogates of income taxes in other colonies (McLean 2012; Sanders, Sandvik & Storli 2019), the failure to institute these early forms of direct taxes had long-term fiscal ramifications at the Cape. The outcome was that public borrowing was accompanied by comparatively higher risk premiums which further strained revenues through higher debt servicing costs.

Public Debt and Risk Premiums

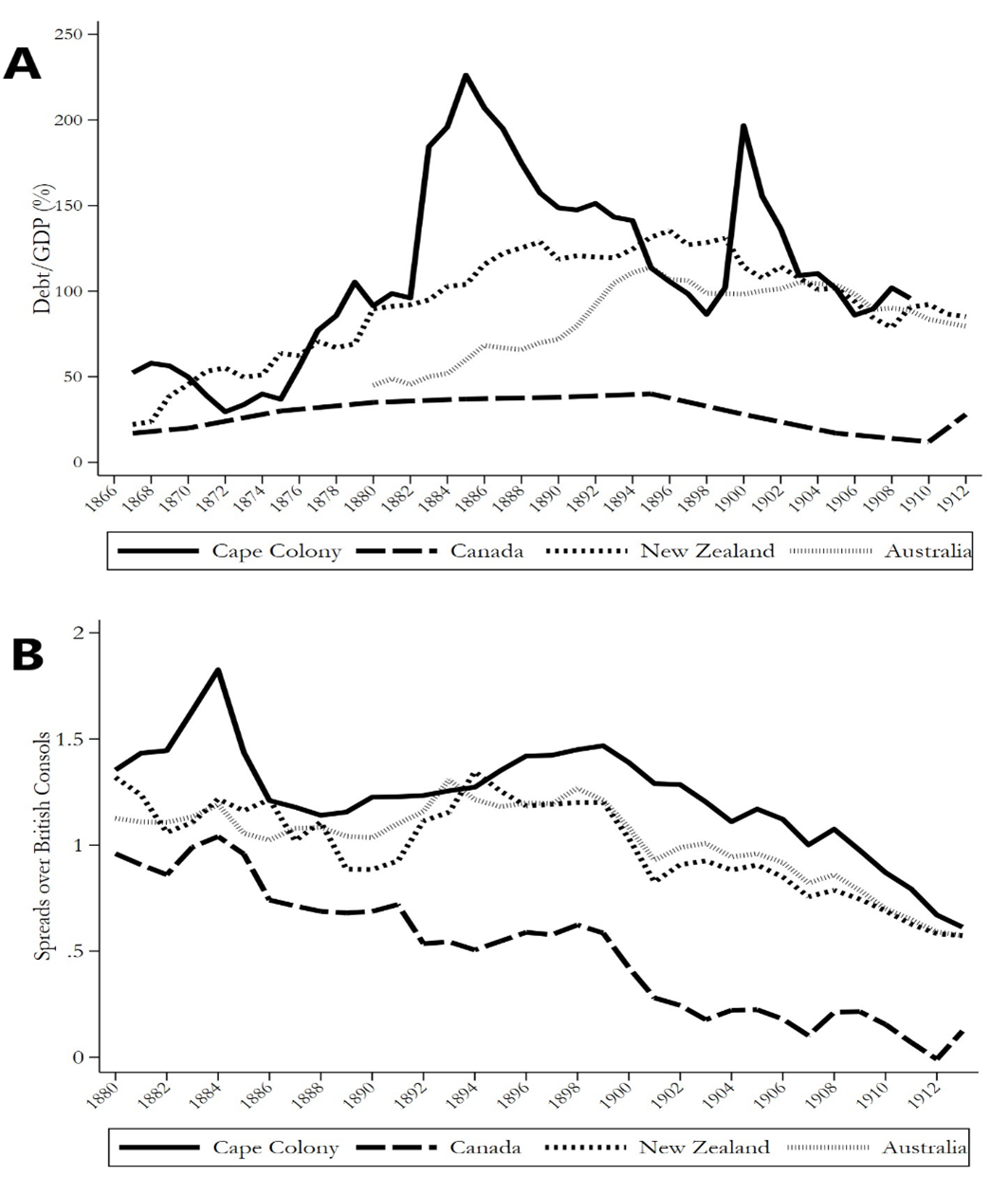

Besides taxation, borrowing was essential for these colonial states to invest in physical capital accumulation. The Economist reported in 1883 that ‘Every year since 1875 has found the Cape government a fresh borrower in the London market […] she has been recklessly extravagant’ (p. 1576). To assess this claim, I measure debt to GDP, bond yields and the spreads over the British consolidated annuities (consols) across the four colonies to trace levels of indebtedness (Figure 3). It is clear in Figure 3 that the Cape accumulated higher debt levels than other colonies. The risk premiums, measured through spreads over Britain’s consolidated annuities (consols), also shows that lenders viewed the Cape as a higher risk borrower, although the risk premium did decline after 1900, as in other colonies.

Figure 3: Debt/GDP ratios and bond spreads

Conclusions

The Cape Colony differed from other settler colonies already in the 19th century, on account of its lower fiscal capacity. I argue that this was a consequence of the interactions between settlers and the Cape’s large indigenous population that resulted in a system of formal economic oppression of the indigenous population and consequently a smaller taxable base. I argue that it is important to balance the institutions debates by accounting for how imported institutions were endogenized in different settings. The ease with which the institutions of “responsible government” were established in other British settler colonies should be considered in the context of the homogeneity of the governed population.

References

Accominotti, O., Flandreau, M., Rezzik, R., & Zumer, F. (2010). Black man’s burden, white man’s welfare: control, devolution and development in the British Empire, 1880–1914. European Review of Economic History, 14(1), 47–70.

Davis, L., & Huttenback, R. (1986). Mammon and the pursuit of Empire: The political economy of British imperialism, 1860-1912. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gwaindepi, A & Siebrits, K. (2020) ‘Hit your man where you can’: Taxation strategies in the face of resistance at the British Cape Colony, c.1820 to 1910, Economic History of Developing Regions, 35:3, 171-194.

McLean, I. (2012). Why Australia prospered: The shifting sources of economic growth. Princeton University Press.

Ross, R., Mager, A. K., & Nasson, B. (2011). The Cambridge history of South Africa volume 2: 1885-1994. The Cambridge History of South Africa Volume 2: 1885-1994 (Vol. 2).

Sanders, A., Sandvik, P., & Storli, E. (2019). The political economy of resource regulation: An international and comparative history, 1850-2015. Vancouver: UBC Press.

Feature image: Railway construction in the Cape Colony, from Elliot Collection in the Western Cape Archives [E7911].