Recent studies have uncovered long-term trends in welfare development in sub-Saharan Africa. But what do we know about the living standards of the large majority of rural dwellers in colonial Africa? Do we have data of sufficient precision and quality to reconstruct economic activity and material welfare in rural areas? This paper proposes a new approach to reconstruct living standards of rural Africans in a historical context with limited data availability, focusing on the case of colonial and early post-colonial Uganda (1915–70).

Quantitative evidence on rural welfare

To reconstruct the long-term development of welfare of rural Africans, we must probe beyond country-level statistics, which are heavily biased toward the formal sector and contain little information on the distribution of economic activity on the level of regions, villages or households. Urban unskilled real wage series have generated insightful comparative evidence about the purchasing power of African unskilled male wages (Frankema & van Waijenburg 2012), but the reliance on formal sector wages and the assumption of an urban male ‘breadwinner’ household limits the suitability of real wages for capturing welfare development among African smallholders.

I exploit different types of data that directly pertain to the living conditions of ordinary households. Gathered from various archives in the United Kingdom and Uganda, the sources include agricultural surveys of villages across Uganda, income and consumption surveys of rural households and unskilled urban and rural wage laborers, annual producer price series of cash crops at the “farm gate,” and annual market price series of local and imported consumer goods in Kampala and trading centers throughout Uganda (the data is presented in an Online Supplement)

Did Uganda’s smallholders thrive?

Soon after the completion of the Uganda Railway in 1902, landlocked Uganda effectuated an impressive cotton- and later coffee-based “cash crop revolution” (Wrigley, 1959), which has received much less attention in the recent literature than its cocoa-based counterpart in Ghana (Austin 2014).

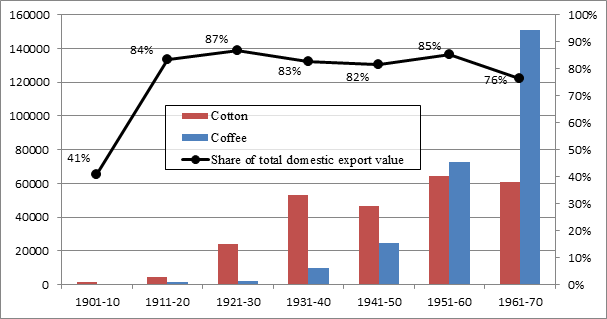

Figure 1: Average annual export of Cotton lint and coffee (in tons) from Uganda, 1901–70

Some peculiar features distinguish Uganda’s “cash crop revolution.” The diffusion of export crops, illustrated in Figure 1, cut across both favourably endowed “forest” and more marginal “savanna” agro-ecological zones. Remarkably, previous urban real wage estimates show that the export crop boom did not result in rising formal sector wages (Frankema & van Waijenburg, 2012). To what extent, then, did Uganda’s smallholders themselves benefit from the cash-crop export boom?

I reconstruct welfare ratios for three types of typical smallholder farms (each growing different food and cash crops) and for unskilled construction worker households in Kampala, expressing their real incomes relative to subsistence level (welfare ratio = 1). Both traded and non-traded agricultural produce are included in the ratio’s numerator, and subsistence needs are estimated using “barebones subsistence baskets,” following Robert Allen’s updated guidelines (Allen 2015).

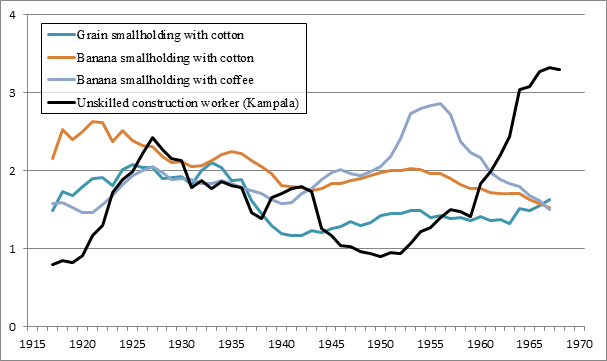

Figure 2: Welfare ratios in Uganda, 1915-70 (five-year averages)

When comparing the welfare ratios in Figure 2, it is important to keep in mind that estimated household labor inputs were substantially lower on smallholdings than in urban settings and more equally spread between men and women. Consequently, even though typical farm incomes were not much higher than those from full-time wage labor, farming was more attractive throughout the colonial era, as evidenced by the overrepresentation in the unskilled labor market of circular migrants from areas with no access to the cultivation of export crops, including many from neighboring Belgian-mandated Ruanda-Urundi. The concurrent take-off of unskilled wages and stagnation of farm incomes during the late colonial and early independence period (1950s and 1960s) is striking. Indeed, contemporaries observed welfare growth in towns and stagnation in the countryside. The share of “stabilized” unskilled laborers (i.e. those who abandoned agriculture and brought their families to town) rose substantially. Those who could not find a job in Kampala returned reluctantly to farming.

From a “dual economy” point of view, this rural-urban divergence seems contradictory. Why would formal sector wages rise if opportunities in smallholder agriculture did not? This study does not attempt to provide a complete answer to this question, but colonial minimum wage policies, which only targeted a small sector of the total labor market, seem to have played a key role. On a methodological note, the preponderance of circular migrants and different real income trends between farmers and wage laborers suggest that caution should be applied when using the (real) incomes of assumed male breadwinner households as a generalized proxy of long-term welfare development, particularly in periods of state intervention in labour markets.

Conclusion

Based on rural census and survey data, this study reconstructed African long-term welfare development in Uganda. The collection of scattered data is labor intensive and may not be feasible for all countries and sub-national regions in colonial Africa. Still, it is a necessary starting point for the reconstruction of economic activity and material standards of living of rural Africans. In the case of Uganda, disaggregated rural data help clarify what a “cash-crop revolution” entailed from the perspective of rural households – a perspective that informs debates about the role of smallholder agriculture in Africa’s past and present development.

References

Allen, Robert C. (2015), “The high wage economy and the industrial revolution: a restatement,”, Economic History Review 68(1), pp. 1-22.

Austin, Gareth (2014), “Vent for surplus or productivity breakthrough? The Ghanaian cocoa take-off, c. 1890–1936,” Economic History Review 67(4), pp. 1035-64.

De Haas, Michiel A. (2016), “Measuring rural welfare in colonial Africa: did Uganda’s smallholders thrive?,” The Economic History Review, online preview.

Frankema, Ewout H.P. and Marlous van Waijenburg (2012), “Structural impediments to African growth? New evidence from real wages in British Africa, 1880–1965,” Journal of Economic History 72(4), pp. 895-926.

Wrigley, Christopher C. (1959), Crops and wealth in Uganda: a short agrarian history. Kampala: East African Institute of Social Research.