Introduction

Historical scholarship often links trade booms with rising coercion, from Eastern European serfdom to plantation slavery in the Americas. Yet many societies operated with more than one coercive labor system simultaneously. My study examines such a dual-coercive environment in nineteenth-century Egypt, where imported slaves and state-coerced local labor coexisted and interacted.

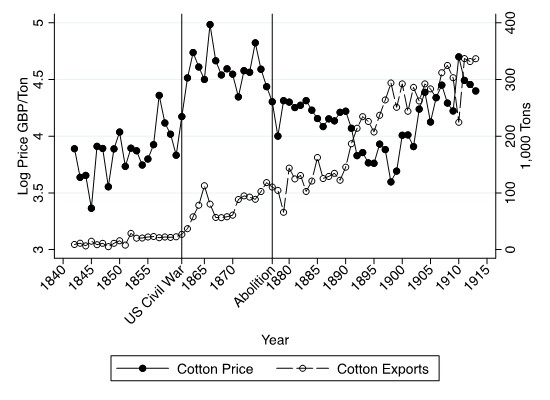

Using newly digitized, nationally representative household microdata from the Egyptian censuses of 1848 and 1868—among the earliest of their kind in the non-Western world—the research investigates how the dramatic cotton price boom of 1861–65 reshaped labor relations. The cotton boom was entirely exogenous to Egypt: American supplies collapsed during the U.S. Civil War, prompting a global search for new sources. Egypt, producer of high-quality long-staple cotton, rapidly expanded cultivation.

Egypt’s Dual-Coercive Labor System

Mid-nineteenth-century Egypt contained four main social groups: (1) elite landholders, owners of large estates with privileged access to state coercion, (2) the rural middle class (mainly, village headmen), agricultural capitalists and medium landholders who could buy slaves but lacked political coercive power, (3) peasants, smallholders relying on family labor, and (4) landless agricultural laborers, supplying wage work.

Imported slaves—mainly black Africans from Nilotic Sudan and Ethiopia—comprised around 1 percent of the population in 1848, mostly females in domestic service. Large estates relied instead on state coercion, compelling local peasants to work without pay. These distinct systems created differentiated labor markets: all landholders could purchase slaves, but only the elite could remove local laborers from the free market through coercion.

Figure 1. Prices and Exports of Egyptian Cotton in 1842–1913

The U.S. Civil War caused a dramatic spike in Egyptian cotton prices and exports

Source: Saleh, 2024.

The Cotton Boom and the Expansion of Coercion

Slave Imports Surge, Driven by the Rural Middle Class

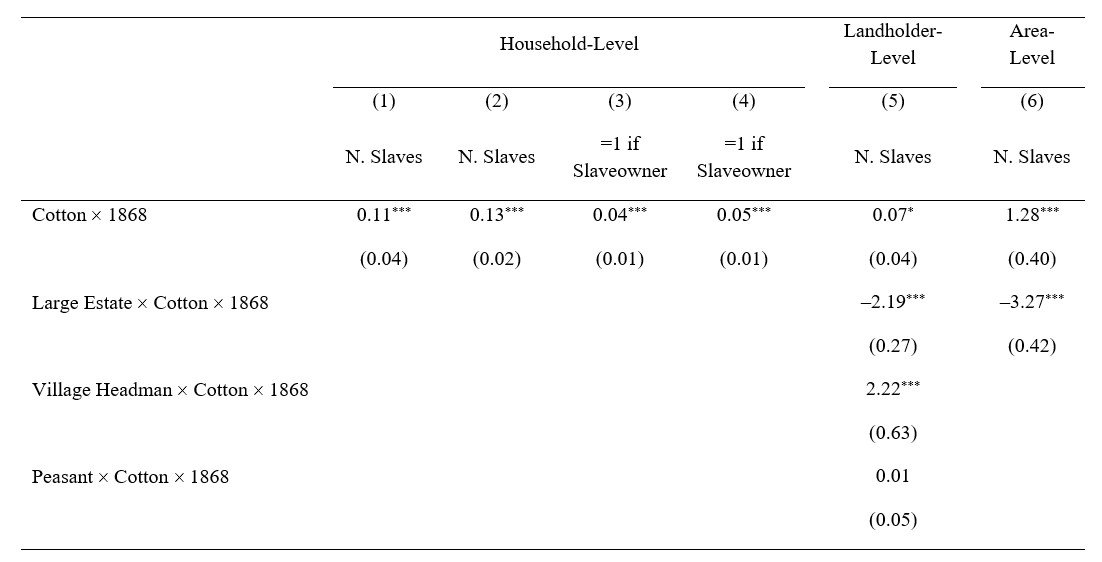

Between 1848 and 1868, the slave population in rural Egypt tripled, rising from 1 percent to 3 percent of the population. Difference-in-differences estimates show that districts more suitable for cotton cultivation experienced significantly larger increases in slaveholdings. The growth was concentrated among village headmen, whose slaveholdings in high-cotton districts rose by about three slaves per household relative to those in low-cotton districts.

This pattern is consistent with the labor intensity of cotton: as demand for labor rose, middle-class landholders purchased slaves to meet it. The gender and age profile of new slaves—predominantly working-age males—suggests their employment in field labor rather than domestic service.

Table 1. The Cotton Boom and Slavery

The cotton boom increased imported slavery, and the rise was driven by village headmen, not large landholders

State Coercion Intensifies Among the Elite

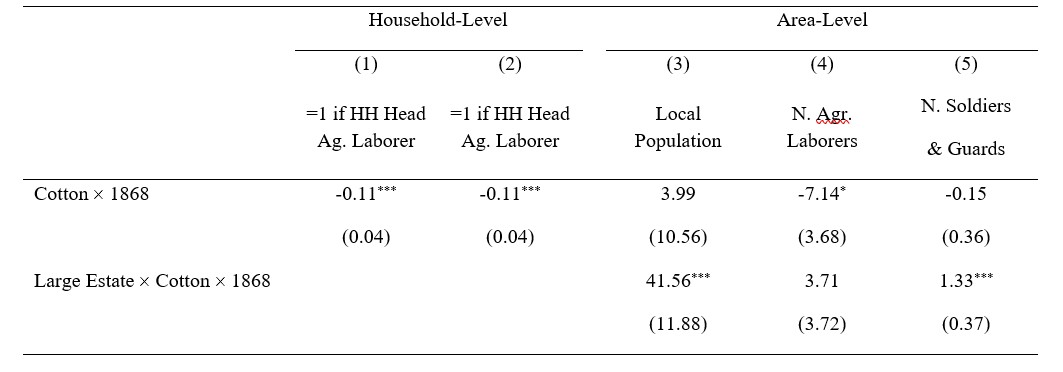

Parallel to rising slave imports, large estates expanded their coercion of local peasants. In cotton-suitable districts, coerced employment on large estates increased significantly between 1848 and 1868. This shift removed laborers from the free market, reducing wage employment in cotton areas.

Table 2. The Cotton Boom, Wage Employment, and State Coercion of Local Labor

The cotton boom reduced wage employment but increased coercion of labor in large estates

Slavery and State Coercion Reinforce One Another

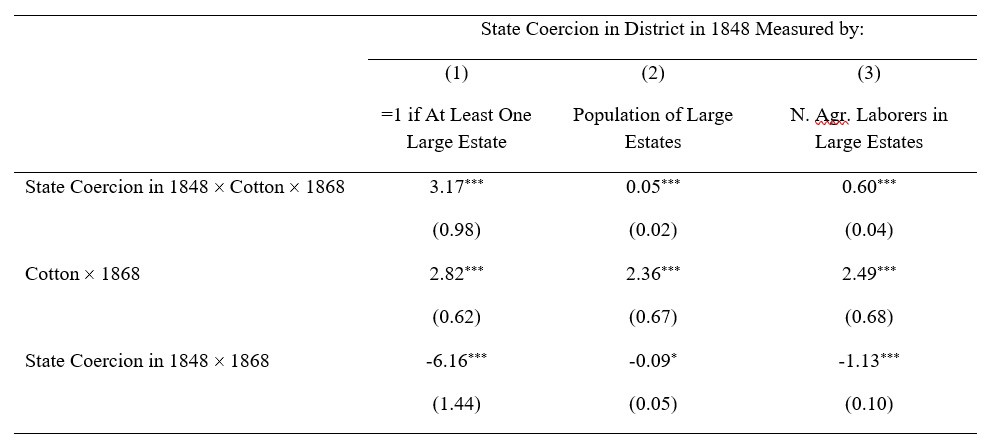

The two coercive systems interacted. In districts where state coercion was more prevalent before the cotton boom, village headmen increased their slave purchases by even larger amounts after 1861. As elite coercion shrank the local supply of wage workers, the rural middle class turned more heavily to slavery.

Table 3. State Coercion Reinforced Slavery During the Cotton Boom

The 1877 Abolition of Slavery

Egypt abolished slavery in 1877 under British pressure rather than domestic political change. The study finds that abolition raised wages, consistent with a tightening of coerced labor supply. Yet abolition did not reduce state coercion or increase wage employment in cotton districts.

One possible explanation is political: after abolition, rural middle-class Members of Parliament began voicing stronger opposition to state coercion, limiting further expansion but not reversing it. While this evidence is suggestive, the available sources do not allow a definitive causal link.

Conclusion

The findings reveal how globalization can intensify multiple coercive labor systems simultaneously. Egypt’s cotton boom strengthened both imported slavery and state coercion, and the two systems interacted to reshape rural labor markets. Abolition dismantled slavery but left state coercion largely intact.

More broadly, the study underscores the importance of examining dual-coercive environments in African and global economic history, where imported slaves and local forms of unfree labor often coexisted and responded jointly to global shocks.

References

Acemoglu, Daron, and Alexander Wolitzky. 2011. “The Economics of Labor Coercion.” Econometrica 79 (2): 555–600.

Cuno, Kenneth M. 2009. “African Slaves in 19th-Century Rural Egypt.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 41 (2): 186–188.

Owen, Roger. 1969. Cotton and the Egyptian Economy, 1820–1914: A Study in Trade and Development. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Saleh, Mohamed. 2024. “Trade, Slavery, and State Coercion of Labor: Egypt during the First Globalization Era.” Journal of Economic History 84 (4): 1107–1144.

Wright, John. 2007. The Trans-Saharan Slave Trade. London: Routledge.

Feature image: Cotton Picking in Egypt. G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection, Library of Congress: https://loc.gov/pictures/resource/matpc.18004/