Theoretical Blind Spots in Slavery’s Economics

Classic models of slavery’s persistence, particularly those developed by Nieboer (1900) and Domar (1970), rely on land abundance and labor scarcity as determining variables. In our new paper, we argue that these frameworks share a core blind spot: they treat slavery primarily as a labor regime and therefore miss its financial logic, namely that enslaved people functioned as collateralizable assets that converted coercion into credit and frontier expansion into capital formation. In these classic frameworks, slavery declines once wage labor becomes cheaper and land becomes scarce. Such theories treat slavery as interchangeable with other coercive systems like serfdom or debt peonage. The literature on coercion cost models shares a similar blind spot: it frames slavery as a generic incentive and supervision problem, and therefore misses slavery’s institutional specificity as a property regime in which laborers were also collateralizable assets (Fenoaltea, 1984). Both fail to account for slavery’s institutional specificity. Enslaved people were not only laborers but also financial assets. Their legal status as property allowed them to be mortgaged, transferred, and foreclosed. This enabled enslavers to use them as collateral in frontier credit markets. Unlike other coercive labor systems, slavery linked labor extraction to capital formation. This makes it functionally distinct and helps explain its durability in capital-constrained environments.

Slavery as Capital Solution in Frontier Economies

United States

In the antebellum American South, enslaved people represented 44 percent of total wealth in the cotton states by 1859 (Martin, 2010). Their role in credit systems was significant. Enslavers routinely pledged enslaved individuals to finance land acquisition, farm expansion, and crop production. Mortgage data from Louisiana and Virginia show that 63 percent of total loan value was secured against human collateral. In some regions, including parts of Louisiana, this proportion was even higher.

The appeal of enslaved people as collateral lay in their portability and standardized value. Unlike land, which was tied to local legal and market constraints, enslaved individuals could be sold or relocated to match credit demands. This made them more liquid than fixed assets and suited to interregional finance. The mortgage market developed around this logic. When emancipation eliminated legal claims over the enslaved, the collateral base underpinning credit collapsed. The financial consequences were immediate and widespread.

Cape Colony

In the Cape Colony, the enslaved were often more expensive than semi-coerced Khoesan labor. Nonetheless, settlers continued to purchase enslaved individuals well into the nineteenth century. Beginning in the 1730s, records show that enslaved persons were used in mortgage contracts. By the early 1800s, they had become the dominant form of collateral in the colony (Ekama, 2021; Worden, 1985). Even settlers without large landholdings accessed credit by leveraging enslaved individuals.

Credit networks were largely informal, relying on private lenders and geographically dispersed markets. Mobility, in such circumstances, was essential. Enslaved people could be moved between districts, giving lenders greater flexibility and borrowers wider credit access. This helped settlers overcome the structural limitations of a land-abundant but capital-poor environment. When abolition was enacted in 1834, many settlers argued that the most severe consequence was the interruption of credit. Martins (2020) finds that grain output fell sharply after emancipation, with 70 percent of the variation explained by capital losses. Agricultural investment was no longer financeable as it used to be.

Brazil

In Brazil, slavery was initially introduced to address acute labor shortages. Portugal lacked population reserves for colonization, and indigenous labor supplies were disrupted by disease and violence. For most of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, enslaved people were not fully mortgageable assets. Legal restrictions prevented their alienation from the properties where they lived and worked. This limited their use as mobile collateral, despite their high value relative to land.

By the mid-nineteenth century, Brazil faced a severe liquidity problem. Land was abundant but difficult to title and use as collateral. Commodity prices were volatile, and crop-based credit was unreliable. The 1864 Law of Mortgages addressed these problems directly by facilitating the exploitation of enslaved individuals in foreclosure proceedings. This change unlocked the financial potential of slave ownership.

In Campinas, the most important coffee-growing region in Brazil, enslaved individuals secured 93 percent of rural mortgage value between 1870 and 1874 (Ribeiro and Penteado, 2020). Planters used this collateral to finance land improvement, machinery, and urban real estate. Banks, including Banco do Brasil, began accepting the enslaved as collateral in their agricultural loan portfolios. By the 1880s, however, slave prices started to fall as abolition became politically unavoidable. The decline in collateral value led to a tightening of credit and curtailed new investment. Many enslavers, including wealthy ones, became insolvent. The abolition of slavery in 1888 formalized a process of financial contraction that had already begun with the erosion of human collateral.

Rethinking Slavery’s Persistence and Collapse

Slavery persisted in these three regions because it provided a viable alternative to the problem of capital scarcity. The labor function of the enslaved was significant, but their financial role was what allowed the system to endure across different legal and economic settings. No other form of coerced labor provided both productive output and convertible value for credit markets.

This insight revises the analytical baseline of traditional theory. Slavery should not be understood solely through labor substitution models or wage competition. Its institutional architecture linked land expansion and labor control to capital mobilization. The collapse of this function through declining prices, legal reforms, or moral-political shifts disrupted access to credit and contributed directly to the system’s failure.

Slavery functioned as a composite mechanism for frontier development, combining coercion and finance in ways that other institutions could not replicate. Its endurance was a response to undercapitalized settler economies.

References

Domar, E.D., 1970. The causes of slavery or serfdom: a hypothesis. The Journal of Economic History, 30(1), pp.18–32.

Ekama, K., 2021. Bondsmen: Slave Collateral in the 19th-Century Cape Colony. Journal of Southern African Studies, 47(3), pp. 437-453

Fenoaltea, S., 1984. Slavery and Supervision in Comparative Perspective: A Model. The Journal of Economic History 44(3), pp. 635-668

Martin, B., 2010. Slavery’s invisible engine: mortgaging human property. The Journal of Southern History, 76(4), pp.817–866.

Martins, I., 2020. Collateral effect: slavery and wealth in the Cape Colony. PhD thesis. Lund University.

Nieboer, H.J., 1900. Slavery as an industrial system: ethnological researches. 1st ed. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

Ribeiro, M.A.R. & Penteado, M.A.A.C., 2020. Escravos hipotecados, Campinas, 1865–1874. Revista de História, (179), pp.1–39.

Worden, N., 1985. Slavery in Dutch South Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

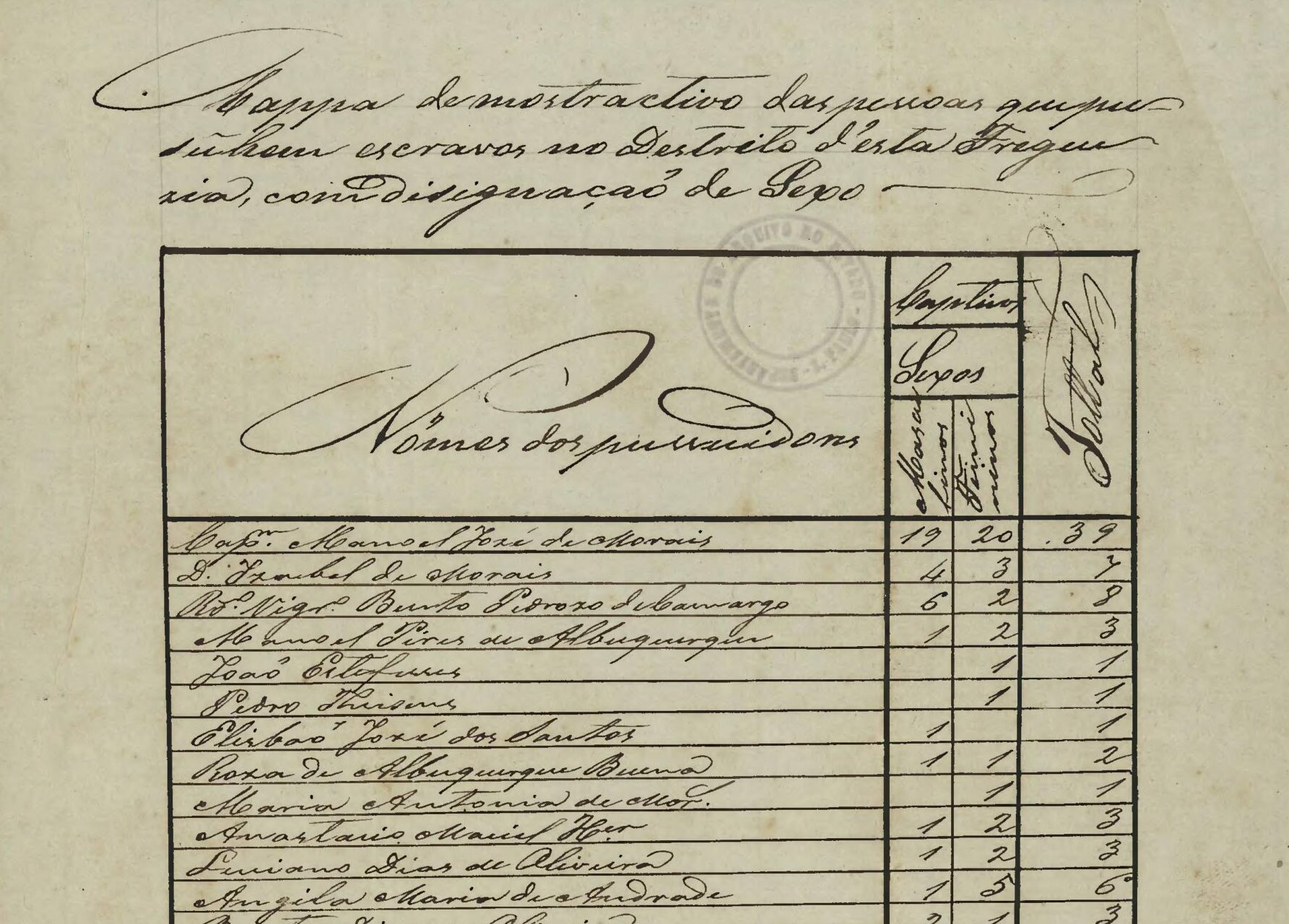

Feature image: Lista de proprietários de escravos da fregesia de Itapecerica, 31 de Agosto de 1850, Arquivo Público do Estado de São Paulo, freely translated as: List of slaveholders of Itapecerica parish, August 31st 1850, State of São Paulo Public Archive.