Introduction: A Crisis Decades in the Making

As South Sudan’s political crisis deepens in early 2025, many fear another civil war is imminent. As I illustrate in a recent article, South Sudan’s conflict cycles are shaped by over a century of coercive and predatory state building practices with long fiscal roots. I show that South Sudan’s revenue raising practices, from British-led colonial rule to the current ruling South Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A) era, have rarely been about state building through public services. Rather, the country has developed what I term a ‘revenue complex’: a system through which rulers exert control, reward loyalty, and finance war.

Colonial and Postcolonial Foundations of Coercive Taxation

During British-led rule (1899–1956), the colonial state scarcely collected tax directly. Instead, it empowered customary authorities to extract tribute and poll taxes. These authorities typically retained a 10% cut and enforced compliance through tax raids, imprisonment, and livestock seizure. These practices were not primarily about revenue generation. As colonial officers admitted, they were political and intended to ‘civilize’ and ‘pacify’ communities through violence and coercion that asserted state presence at minimal cost.

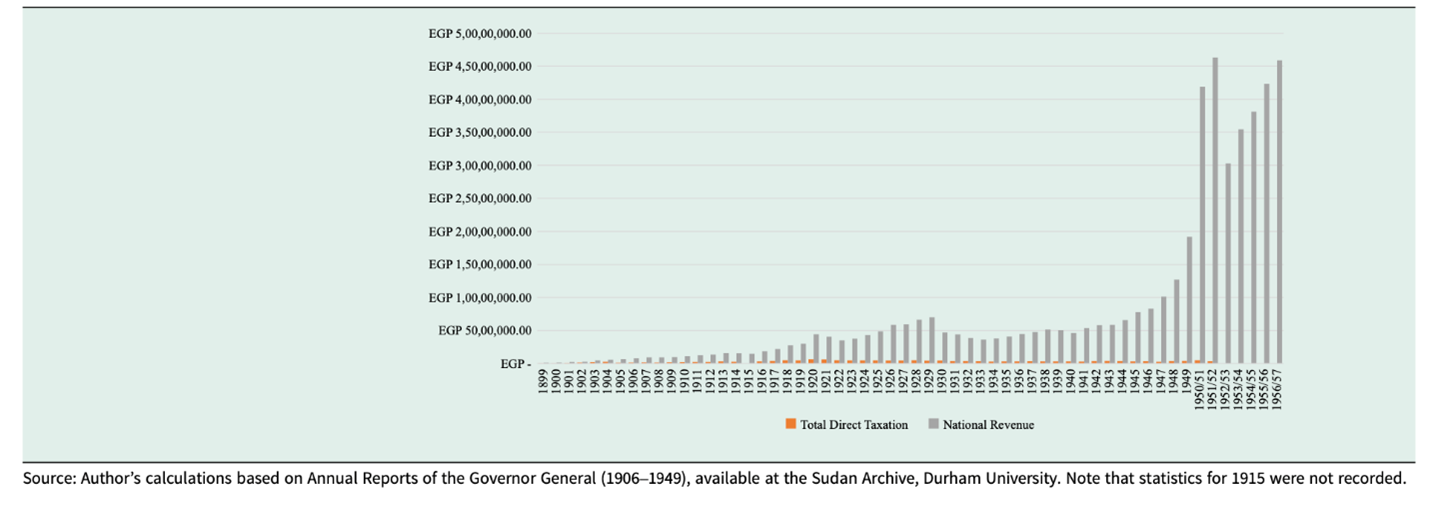

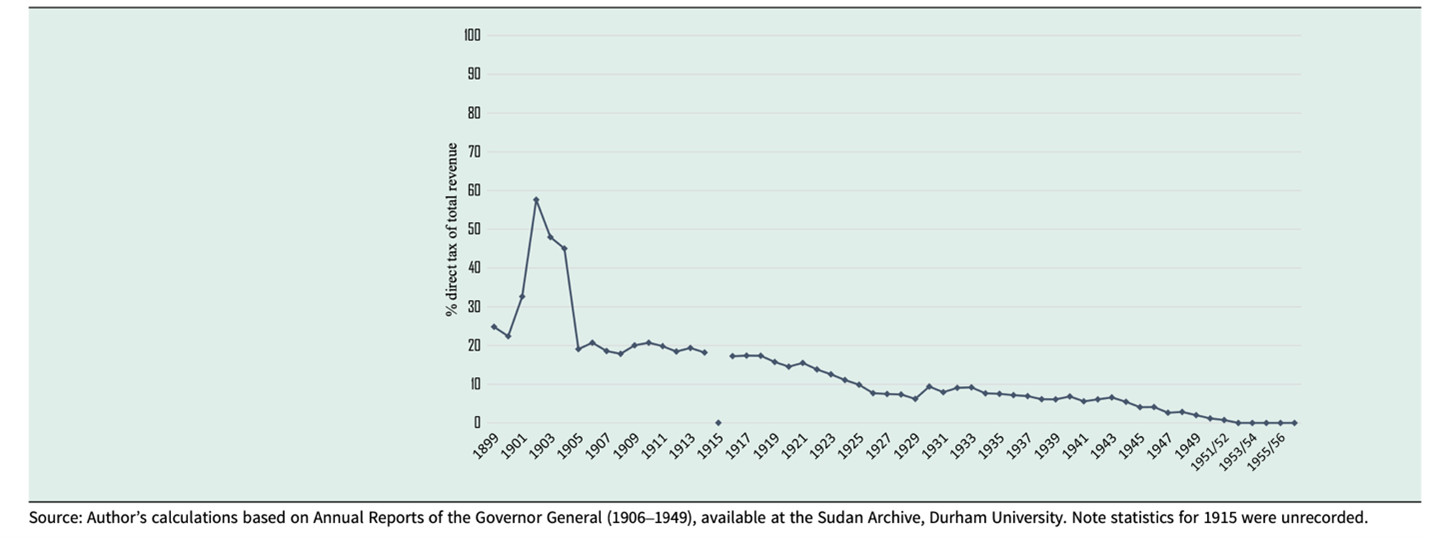

The post-independence Sudanese state was unified with South Sudan and perpetuated these patterns. Although direct taxes comprised only a small share of overall revenue (see Figures 1 & 2), they played a disproportionate role legitimating state authority and attempting to territorialise the region’s diverse populations, several of which were nomadic. As colonial and postcolonial administrators relied on cotton exports and external finance, taxation remained politically symbolic rather than fiscally significant. My archival research in Sudanese, South Sudanese and British archives shows that while direct taxes were fiscally marginal, they were central to how power was exercised and legitimized in the south.

Figure 1. Total Revenue and Direct Tax Revenue in Egyptian Pounds, 1899-1956

Figure 2. Percent Direct Tax of Total Revenue, 1899-1956

Figure 2. Percent Direct Tax of Total Revenue, 1899-1956

Tax as a tool of rule continued even during postcolonial experiments with semiautonomous Southern Sudanese rule from 1972-1983. An attempt to formalize revenue collection through a ‘social service tax’, locally known as mocoro, emerged in this period. Though intended to support local development, mocoro entrenched coercion during peacetime.

Rebel Taxation and Predation Logics

During the SPLM/A’s long insurgency (1983–2005), colonial predatory taxation practices were retrofitted instead of abandoned. In areas under rebel control, commanders imposed levies on cattle, crops, traders, and river traffic. While some practices were routinised, taxation often operated through coercion or obligation rather than bureaucratised systems.

In 205 interviews I conducted with a South Sudanese research network, rebel taxation was consistently described as extractive. One former administrator explained that SPLM/A units collected food and cattle from households, often via chiefs, and justified it as a war struggle contribution. But refusal had consequences. Terms such as muun koc or kutkut were used in Gogrial East County, which translate to ‘taxes for the people’; but both were ‘forceful taxes’ whereby SPLM/A soldiers seized cows without consent.

Rather than channelling revenue to a central rebel authority, taxation remained localised. The SPLM/A’s fiscal reach was uneven, with commanders absorbing revenues and operating autonomously. The logic mirrored the colonial era in which taxation functioned as tribute instead of a broader redistribution system. For example, in what is now Warrap State, the SPLM/A’s forced recruitment was known as catcha, which comes from the English word ‘catch’ and refers to forced recruitment into the rebel military. It was a localised, often improvised form of rebel governance that sustained fighters and signalled territorial control.

Today’s Crisis and the Weight of Fiscal History

Institutions formed after the 2005 peace agreement and 2011 independence became rent-distribution systems with few formal constraints. This is an oft-overlooked fiscal problem and not merely a political one. As oil revenues decline and international donor fatigue grows after more than a decade of international support to the country’s public services, the state’s reliance on coercive taxation has deepened. As research by Joshua Craze (2025) shows, local officials continue to collect taxes outside formal channels, while the oil-dependent national budget remains opaque. What the history of taxation in South Sudan reveals is that today’s governance crisis is not new. It is the culmination of over a century of using taxation as a tool of domination, not development.

Conclusion: Toward a Different Fiscal Future

Avoiding another devastating war will require more than elite power-sharing. It necessitates confronting the fiscal architecture that has long enabled coercion, fragmentation, and elite rule through privileged access to wealth. Seemingly apolitical technical fixes will not be enough. Instead, reform must begin with a shift in the meaning of taxation itself, from a practice of rule to a public good. This vision aligns with how many South Sudanese imagine taxation should function, despite few historical examples of it practically working. As we navigate South Sudan’s uncertain present, understanding the country’s revenue complex is crucial not just for diagnosing its past, but for forging a more stable future there and in other predatory African countries across the continent.

References

Benson, M.S., 2024. Of rule, Not Revenue: South Sudan’s Revenue Complex from Colonial, Rebel, to Independent Rule, 1899 to 2023. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 66(1), pp.110–142.

Craze, J., 2025. What is Happening in South Sudan? African Arguments, 13 March. Available at: https://africanarguments.org/2025/03/what-is-happening-in-south-sudan/ [Accessed 4 Apr. 2025].

Feature Image: SPLM propaganda flyer. Sudan Archive at Durham University – SAD.985/4/87.